Claytonia perfoliata species complex on the Tejon Ranch — this is only the beginning of your Montiaceae-related nightmares…

The taxonomy for the annual species of Claytonia (section Limnia) is VERY difficult to work with, mostly because diagnostic characters are not well preserved on herbarium specimens. Unfortunately, a molecular phylogeny that spells out the relationships among taxa in this group is still lacking, but I have added many samples as out-group taxa for my own dissertation studies on section Claytonia (i.e., the tuberous perennial Claytonia)… Is the cause for confusion in field identification due to phenotypic plasticity, hybridization, or both? Is it something else altogether, such as the rapid formation of localized ‘races’ due to poor dispersal capabilities? If the difficulty of accurate field identification is due to hybridization, is this a problem? For taxonomy, the morphological consequences of hybridization are an issue that must be addressed, but for the longevity of lineages, hybridization is probably not a ‘problem’ but rather a solution — it might just be the key to sustaining genetic diversity and promoting adaptation in a forever changing climate — evolutionary success! Before I get too deep into the hole I am digging, we’d better take a look at some nice plant images to really smell what I am stepping in 😉

Claytonia parviflora subsp. viridis — Tejon Ranch. Note the linear basal and cauline leaves of this mildly succulent annual. Were you to collect, you could rest easy with ID of this plant.

Claytonia parviflora subsp. viridis X C. rubra ?!?!– Tejon Ranch. Note the non-linear basal and cauline leaves of this moderately succulent annual, and the floral morphology of C. rubra. Yet, this plant retains the fully separate leaf pair of C. parviflora subsp. viridis.

Claytonia parviflora subsp. viridis X C. perfoliata ?!?! — Tejon Ranch. Note the spatulate basal leaves. I certainly wouldn’t want to be doing a flora of this area, as I’m sure this isn’t the only group with these kinds of ‘problems’ with hybridization 😉

Claytonia exigua (left) and C. exigua X C. perfoliata (right) ?!?! — Tejon Ranch. Note the glaucus basal leaves of the plant on the right, which should otherwise look like the plant in the first picture of this post. Yikes!

More fun with sympatry on Tejon Ranch!!! Left to right, Claytonia exigua, a diminutive C. perfoliata, and something that approaches C. rubra in morphology — section Limnia is tough!

Could this possibly even be the same as any taxon we’ve seen elsewhere in this blog post? I’m really not sure, but I would lean toward calling it C. perfoliata-like. The C. perfoliata complex, including also C. rubra and C. parviflora, is probably the most difficult group in section Limnia.

This is also Claytonia perfoliata! Its first leaves are narrow like these. Under drought conditions it can ‘bypass’ switching to the more mature spatulate leaf condition by going directly into flowering and therefore only producing the perfoliate cauline leaves.

Contrast (or compare, in case of my suggested hybrids) the above pictures with this one of Claytonia rubra — this appears to be a good example of this species which at one point was treated as C. perfoliata but has been found to be a unique lineage and is treated as such.

Now, compare the picture immediately above (of Claytonia rubra subsp. rubra) with this one — same or different?! Same! Well, sorta… This is ALSO C. rubra, presumably subsp. depressa, which apparently also occurs on the Tejon Ranch — how exciting!

Okay, so interestingly enough, I took all of these photos (and many, many, many more) in only one day on Tejon Ranch with Nick Jensen, a colleague at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden doing a floristic study of the area. His website can be found here. This is a fascinating area because it serves (or, served) as a biogeographic traffic signal for the Sierra Nevada, the Transverse Ranges AND the San Joaquin Valley and the Mojave Desert. I suspect the evidence for hybridization exhibited by the numerous sympatric Claytonia here is mirrored in other plant groups on the Tejon Ranch where multiple taxa co-occur.

But that isn’t all, of course — the evidence of hybridization reappears in every mountain range I have explored in southern California! It seems to be a battle among divergent lineages to survive and compete for overlapping and limited niche space near the southern part of the geographic distribution of these plants, but maybe a little cooperation wouldn’t hurt for the ‘greater good’ of Claytonia if it increases genetic diversity… In the San Bernardino Mountains, you can find members of the C. perfoliata species complex in sympatry. The evidence for hybridization in this area mirrors what I observed at Tejon Ranch.

From left to right, Claytonia parviflora, C. perfoliata and C. rubra, all members of the C. perfoliata species complex occurring together in Mill Creek Canyon, San Bernardino Mountains.

A good example of Claytonia parviflora; note the erect, linear basal leaves that are almost terete in shape, and the cleft in the disc-like cauline leaf-pair resulting from incomplete fusion of two leaves.

Compared with the picture immediately above, this one looks like a fusion of C. parviflora and presumably one (or both?) of the other two annual species in the area. I tend to think C. perfoliata may have played a role in the formation of this hybrid, but we can only be sure by DNA sequencing or by extensive cytological screening. Note the erect basal leaves that are no longer linear in shape but instead have rather distinct blades — this is NOT C. parviflora in the strictest sense of the name.

In the San Jacinto Mountains, you can find more of the same — members of the C. perfoliata species complex in sympatry and evidence for hybridization that may make you want to tear your hair out if you are working to identify plant specimens collected here. For instance, the pictures below from the San Jacinto Mountains are more or less taken from within ~1 contiguous square mile in Garner Valley.

An excellent example of C. parviflora subsp. viridis is strutting its stuff roadside in the San Jacinto Mountains. Here, you have more action in the ring coming from the C. parviflora corner than from elsewhere in the C. perfoliata complex — I’m not sure the reason but think it is related to the locality I visited, a recently burned area in Garner Valley with little overstory cover.

Compare the picture immediately above (of C. parviflora subsp. viridis) with this one of C. parviflora subsp. parviflora — similarly erect basal leaves that approach a terete-linear shape, but a contrastingly perfoliate cauline leaf-pair that is almost completely fused (as opposed to the free cauline leaves of C. parviflora subsp. viridis photographed above). The two appear to have different coloration under the same conditions here as well in both the flowers and foliage. — Garner Valley, San Jacinto Mountains.

Now, compare the picture immediately above (of C. parviflora subsp. parviflora) with this one of some sort of C. parviflora hybrid — similarly erect basal leaves but these appear to be forming distinct blade and petiolar regions unlike the other two photos above from the same general location… tempting to call them the same, but I imagine this fishiness has both rhyme and reason to it. — Garner Valley, San Jacinto Mountains.

This plant is OBVIOUSLY different from the rest, but what do you call it?! Under some Jeffrey pines that survived the fire, these plants approach the morphology of C. perfoliata subsp. mexicana but the smaller leaves in the center of the rosette are suggestive of certain races of C. rubra. — Garner Valley, San Jacinto Mountains.

What a wild and wacky world we live in! Claytonia will keep me busy (and happy) for many years to come…

… so maybe we should start with a survey, to see what you think. How many cotyledons do you think Claytonia have? Keep in mind, they are dicots.

… so maybe we should start with a survey, to see what you think. How many cotyledons do you think Claytonia have? Keep in mind, they are dicots.

If you guessed that Claytonia have 2 cotyledons, you’re right… but you’re not the only one that is right. Technically, those of you that guessed Claytonia have only 1 cotyledon are also correct — that’s right, there is in fact a group of dicots with only 1 cotyledon (probably several, but that question exceeds the scope of this blog post). Claytonia Section Claytonia, otherwise known as the tuberous perennials, lack a second cotyledon present in other species of Claytonia (and all of their closest relatives). To me, this is just another reason why you should believe that Claytonia is the whackiest group of plants this side of the Mississippi River. 😉

If you guessed that Claytonia have 2 cotyledons, you’re right… but you’re not the only one that is right. Technically, those of you that guessed Claytonia have only 1 cotyledon are also correct — that’s right, there is in fact a group of dicots with only 1 cotyledon (probably several, but that question exceeds the scope of this blog post). Claytonia Section Claytonia, otherwise known as the tuberous perennials, lack a second cotyledon present in other species of Claytonia (and all of their closest relatives). To me, this is just another reason why you should believe that Claytonia is the whackiest group of plants this side of the Mississippi River. 😉 So who cares, there has been a loss of one of the cotyledons in this group of plants. One time only evolution, and now these plants simply can’t recover that lost cotyledon — I’m over it… right? WRONG! There is something fishy going on here, and it has to do with a certain caudicose perennial I have mentioned before: Claytonia megarhiza (pictured below).

So who cares, there has been a loss of one of the cotyledons in this group of plants. One time only evolution, and now these plants simply can’t recover that lost cotyledon — I’m over it… right? WRONG! There is something fishy going on here, and it has to do with a certain caudicose perennial I have mentioned before: Claytonia megarhiza (pictured below).

You can see from the second image (the photo immediately above) that Claytonia megarhiza clearly has two cotyledons, not one like the tuberous, perennial Claytonia species I mentioned before. Thus, you’d expect that this species is more closely related to those other Claytonia that have two cotyledons, right? Well…

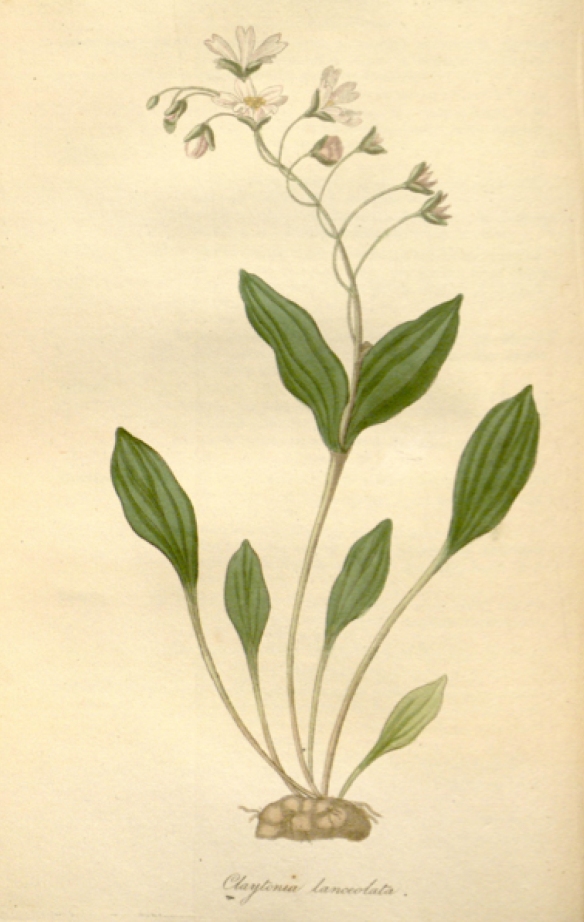

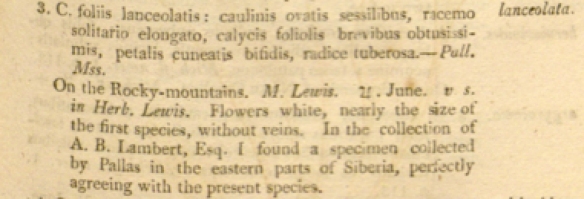

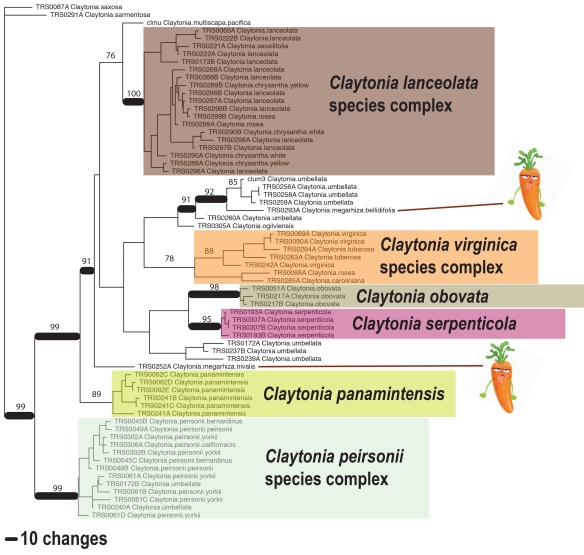

You can see from the second image (the photo immediately above) that Claytonia megarhiza clearly has two cotyledons, not one like the tuberous, perennial Claytonia species I mentioned before. Thus, you’d expect that this species is more closely related to those other Claytonia that have two cotyledons, right? Well… Above is a preliminary phylogenetic tree that I presented at the Botanical Society of America Meeting this year in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. This tree has been developed from ~500 single nucleotide polymorphisms isolated from the nuclear genome of all of the samples included (using ddRADseq). You can see from the tree that the caudicose perennial C. megarhiza (indicated by [morphologically similar, but anatomically quite different] cartoon carrots ) clearly has a close association with the tuberous, perennial Claytonia, albeit the exact area in the tree where they will stabilize is still yet to be determined. Without question, Claytonia megarhiza is nested somewhere in this clade of otherwise tuberous, perennial Claytonia.

Above is a preliminary phylogenetic tree that I presented at the Botanical Society of America Meeting this year in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. This tree has been developed from ~500 single nucleotide polymorphisms isolated from the nuclear genome of all of the samples included (using ddRADseq). You can see from the tree that the caudicose perennial C. megarhiza (indicated by [morphologically similar, but anatomically quite different] cartoon carrots ) clearly has a close association with the tuberous, perennial Claytonia, albeit the exact area in the tree where they will stabilize is still yet to be determined. Without question, Claytonia megarhiza is nested somewhere in this clade of otherwise tuberous, perennial Claytonia.