Hi, all — I’ve decided to switch things up and simply chat with you a bit about a topic that has apparently been the most popular on my blog so far: Claytonia rubra (Howell) Tidestrom. You may find yourself now asking the question, “Claytonia rubra, what is that?” Well, there’s a blog post for that.

Claytonia rubra photographed while flowering, plants growing abundantly in the Pinyon-Juniper belt on the Modoc Plateau, northern California.

But Claytonia rubra may be more than meets the eye, especially if you’ve been paying close attention to it where it grows in different areas, or if you’ve been so lucky as to see it from across its entire geospatial distribution. Let’s think about this for a minute, considering first the global range of Claytonia rubra.

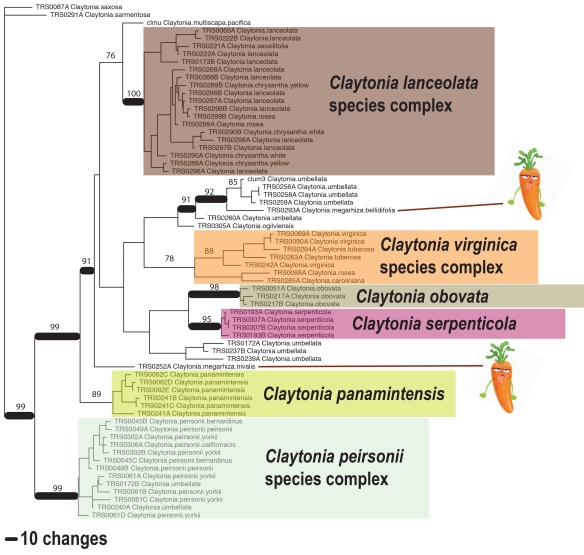

It is across this wide and ecologically diverse distribution, north to south from British Columbia to near (probably in) Mexico, and west to east from the San Francisco Bay Area to the Black Hills of South Dakota, that the annual Claytonia rubra displays a seriously diverse range of morphologies. Is it phenotypic plasticity? Is it local adaptation? Is it speciation? Is it hybridization? Is it some mix of all of these? Claytonia rubra is a tough cookie to crack!

Claytonia rubra photographed while flowering on the Modoc Plateau, northern California. Notice the largest leaf blades (outermost in the rosette) are among the first to have emerged in early development — These lay flat on the ground surface (or nearly so)

Starting with identification, something I’ve found to be fairly characteristic of Claytonia rubra is that its older leaves (outermost in the rosette of basal leaves), which often have the largest blades, tend to lay flat on the ground — some close relatives (like certain subspecies of C. perfoliata) do this too, or something like it, so don’t take this for a smoking gun. Furthermore, some races of C. rubra do not have basal rosettes that lay flat, rather they are elevated ever so slightly above the forest floor. Don’t you just love those kinds of dichotomous key breaks? — Is is erect to ascending (sometimes spreading), or ascending to spreading (sometimes erect)?! — Still, if you see something in the mountains of western North America like in the picture below, where the outermost (older) leaves in the basal rosette lay flat, appressed to the ground, you can be fairly confident that you are looking at something that is quite appropriately called Claytonia rubra.

Vegetative Claytonia rubra photographed at the Tejon Ranch in the Tehachapi Mountains, southern California.

For effect, compare the leaves of Claytonia rubra plants in the above picture with the leaves of the plant in the picture immediately below, C. perfoliata, both of which were photographed at the Tejon Ranch in somewhat close proximity (either side of the same mountain ridge) — see how Claytonia perfoliata (below) tends to elevate its leaves off the ground?

Vegetative Claytonia perfoliata photographed at the Tejon Ranch in the Tehachapi Mountains, southern California.

The characteristic of Claytonia rubra have low-growing leaves seems pretty useful, until you come across a putative lineage (sometimes in the same mountain range!) that looks like the plant below — these plants have distinctly erect / ascending leaves, although the proximal portion of their petioles are still appressed to the ground. This gives the leaves a sort of ‘S-curved’ look. Believe it or not, these are another subspecies of Claytonia rubra!

Claytonia rubra photographed while flowering at the Tejon Ranch in the Tehachapi Mountains, southern California.

This is a time where it comes in handy to know a few other characters that, when used in combination, can help to distinguish Claytonia rubra from similar-looking miner’s lettuce.

Classic, beet-colored (reddish to purplish) undersides of basal leaves of Claytonia rubra. Whenever possible, try to observe this character in multiple plants — Generally, the basal leaves should be deep green adaxially and reddish abaxially in Claytonia rubra.

For example, the plants photographed above demonstrate another conspicuous characteristic of most lineages of Claytonia rubra — betalain pigmentation is generally evident on the abaxial (lower) surfaces of the basal (and sometimes cauline) leaves, giving them a purple/reddish appearance. This is a sort of ‘no-brainer’ character I tend to point people towards, but just as with the characteristic basal leaf orientation I mentioned above, this morphological character doesn’t always hold true. Plants love exceptions WAY MORE than rules: in this particular case there appears to be an environmental element to variation in Claytonia betalain pigmentation, as evidenced by some unpublished observations I have made in common garden experiments involving C. perfoliata, C. rubra, and some perennials in the C. “peirsonii” complex.

Variegation on foliage characteristic of some lineages of Claytonia rubra.

OK, so the leaves are sort of laying flat, and kinda red undeneath, but you’re still not totally convinced you are looking at Claytonia rubra and not some other similar-looking miner’s lettuce. Well, you’re in luck — I’ve noticed that many races of Claytonia rubra tend to have the look of variegated leaves, possibly related to a breaking up of the cuticle during development. If you see something like the plant in the picture(s) above, where there are variegated streaks on the leaves of a Claytonia, it is VERY likely that you are indeed looking at Claytonia rubra.

[From left to right, Claytonia parviflora, C. perfoliata, and C. rubra!] Multiple miner’s lettuce species growing in sympatry in Mill Creek Canyon, San Bernardino Mountains, California.

IF you still can’t be sure about which

Claytonia you are looking at — just ask me! That’s what I am here for…

Doesn’t the above (or below) picture look like a fun place to do a plant survey? I thought so… until I did it, that is.

Doesn’t the above (or below) picture look like a fun place to do a plant survey? I thought so… until I did it, that is.